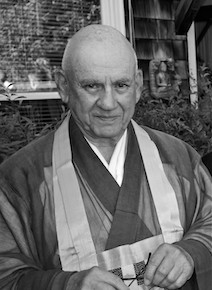

Way-Seeking MindMarch 21, 1997 |

Way-seeking mind is a deep intention to align oneself with a true path. Suzuki Roshi used to call it "our inmost request." We say "get ride of desire" but we can't really get rid of desire. When desire is in conformity with out deepest request, then it's no longer called desire, it's called way-seeking mind. I was born in 1929 to Jewish parents, but I didn't have a real Jewish upbringing. It was quasi-cultural. My parents...weren't so much interested in being Jewish, but they would always speak Yiddish to each other when they didn't want us to understand what they were talking about, which I felt was cheating us. I didn't have a religious upbringing, but I was curious. One day when I was about ten or twelve, we were riding in the car and there was an issue of Life magazine with picture of Hasidic rabbis on the cover. I looked at those rabbis and I immediately felt a tremendous affinity with them. Seeing those Hasids was a jolt that stayed with me; it probably aroused my way-seeking mind. I came to San Francisco and went to art school and met...my first wife. While we were living together...I started reading spiritual literature. One of my wife's friends who was kind of a recluse with a white beard used to hang out at George Fields' bookstore on Polk Street where they had Buddhist and metaphysical books. Sutter Marin, who was a painter, introduced me to him and said that he could show me how to meditate. I was interested in meditation, so I went to his apartment. We would sit. I would look at an object and get into a meditative state. That was my first experience with meditation. He had no particular orientation. He was an open person and he would listen to anything I had to say. He suggested things for me to study or read, depending on what I was interested in. He stimulated me to pursue this desire that I had. I became interested in Judaism and wanted to explore Jewish roots. I found a rabbi from Germany, but he wasn't interested in what I was interested in. I had just discovered Tales of the Hasidim by Martin Buber and I was looking for somebody like in those tales — I was looking for what was called a tzaddik, a holy man. Hasidism was completely out of favor with most Jews at that time. I was living in San Francisco and had no intention of going anywhere else. I had never really traveled — traveling was out of the question, because whatever I was looking for, I felt that I should find it right here where I am. It never occurred to me to go someplace else to find what I was looking for. I was kind of naïve. I did some study of Judaism and I was very turned on in my own way. I reconciled what Judaism was for me. I always felt that the Judaism that I was practicing was true to me, but that I just couldn't make it in the Jewish world because I wasn't Jewish enough. I also felt that being Jewish in the way that many Jewish people are Jewish was too exclusive. All my life I had been associating with the non-Jewish world and I felt that my spiritual life included Judaism but didn't stop there. I was interested in religion, period. I was influencing many of my friends who were artists. I was seeing that as an artist I was trying to express this feeling I had, but I knew that I had to somehow get beyond art in order to find what I was looking for. There were definite influences that led me to think about Zen. We knew Phil Wilson and we had a number of artists friends who started sitting at Zen Center. I read D.T. Suzuki and the Diamond Sutra and a few other things that were published, and of course, the Platform Sutra. The Tao Te Ching was also influential. Many different kinds of books influenced me. One time a friend and I stayed up all night. He told me he had been going to the Zen Center early in the morning for some months now and that there was a Zen priest there. We stayed up all night... Zazen was at 5:45 a.m. so we walked up Fillmore Street early in the morning and went to the Zen Center. I remember walking into a bare, beautiful room. There were some tatamis around the edge, no goza mats, no zabutons. Walking and sitting down on the tatami, facing the wall, and then not quite knowing what to do. But there I was. Somebody came up behind me and adjusted my posture and showed me the mudra. It was Suzuki Roshi. I felt wonderful just to be sitting there. Then we got up and had service and bowed and chatted. It was very strange and then I left. I went back periodically. There was a strong pull to continue going back and I started sitting regularly. After a while I found out who the priests were: "Reverend Suzuki" and "Reverend Katagiri." At some point, I had a revelation — maybe it wasn't such a revelation, but was more a feeling of the inevitable — that this was what I had to do, that this was what I'd been looking for. So I just continued and I've been doing it ever since. By the time I started sitting, I was thirty-five already. I said to myself, "This is it. I have to stay with this, because I know this is it. If I don't stay, I know I'll just stray off someplace." So that's the story. Short story. A few more memories: once, when I was a teenager, I was walking through a parking lot — I get things walking through parking lots — and I suddenly had this feeling that the events of my life, the things that were happening, were not my true life; that my true life was more subjective and internal and was not something that was affected by those events, but was separate from what was happening, like going to school and relating to my parents and friends. There was something that was deeply different or separate from those events that I felt was my true life. I think later I identified that perception as my way-seeking mind, or deeper intention. I like to call it deep intention, or true intention, which wasn't being addressed by any of the events in my life, and that was a kind of awakening. There were also a few times when I was going to art school — once when I was sitting on my bed — that for no reason everything dropped away. I felt an incredible tranquility or lightness. It's impossible to describe what I felt. I thought, "Wow!There's more to life than these events!" I felt that several times. Those kinds of experiences made all the other events of my life seem very pale in comparison &mdash not meaningless but not so meaningful...My parents never approved of what I did in any enthusiastic way. One night I had a dream &mdash this probably was when I was in my early forties &mdash that we (my family and I) were in this heavenly place, in golden light. We all had our arms around each other, which is something we never would have ordinarily even thought of doing. And we were nodding and saying, "Of course, of course." After that dream, I always felt reconciled with them without ever mentioning it to them. After that dream I felt more forgiving. I don't think I've ever held grudges since then. Somehow it was a big opening, that dream. Suzuki Roshi asked me to be ordained in 1967 and then he ordained me in 1969. But I think from the time I started practicing, practicing became the center of my life. I stopped painting before I started practicing Zen. I was playing music at the time, but I never felt a conflict because I could always put the music aside and yet keep it going too. But painting...painting is a way of life. You step into the middle of the canvas and the expression is the painting. It's a way of life, just like Zen is a way of life. I couldn't do both of those things at the same time. Suzuki Roshi used to give me koans, informally, "What is it?" is a koan I've always worked with and "Just being alive is enough." © 1997 Sojun Mel Weitsman |