|

I am happy to be here this morning and see all of you again. This weekend I am going to comment on two Soto Zen teachers: Dogen, and Rujing, who was abbot of Tiantong monastery and who was Dogenís teacher. Rujing wrote quite a bit but we donít have much that is translated. But we do have a recently translated book of Rujingís practice instructions which are not your usual practice instructions. Iíll get to that in a moment. Usually, we study Dogenís Shobogenzo; itís a profound philosophical writing. But Iím going to comment of Dogenís Shobogenzo Zuimonki which is his informal evening talks transmitted by his disciple Ejo. These talks are more off the cuff: people have questions and heíll answer these questions in not such a formal way. We get a picture of Dogen speaking to his students and of his way of relating to people. It gives us another view of Dogen. This morning, I am going to read from the Zuimonki, then this afternoon from Rujing. It is very hard to decide what talk to start with because there are five talks in the book and lots of short pieces. But I am going to start with an evening talk which is basically about doing one thing well, which is Dogenís bottom line. He says even worldly people, rather than study many things at once without really becoming accomplished at any of them, should just do one thing well. |

|

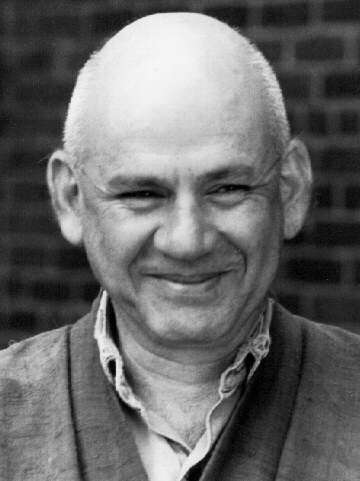

Monastic Weekend Talk

Talk 1, part 1 Talk given to the Chapel Hill Zen Center, March, 1993 |

|

|

In other words, instead of doing a lot of things not so well, do one thing thoroughly. In this exalted and far-reaching Buddha Dharma, if one takes on too many things at once, it would be impossible to perfect even one thing. Even concentrating solely on one thing, those whose capacity and faculties are dulled by nature will have difficulty in fully mastering it." Then he says, "Strive students to concentrate on one thing alone." So even doing one thing thoroughly is difficult enough, much less doing a lot of things. Also, again, he is talking about how you donít have to be really intelligent, you donít have to know a lot. It doesnít depend on whether you are intelligent or stupid or unlearned, but on just concentrating and single-mindedly doing one thing and you will be successful. So Ejo his student asked: "if so, then what thing, what practice in the Buddha Dharma should we be solely devoted to cultivating?" Dogen replied, "Although it should be in accord with potentiality and conform to capability, that which is now transmitted and fully practiced in the school of the ancestors is sitting meditation. This practice takes in all potentials and is a method which can be practiced by those of superior, middling and inferior faculties alike." Anybody can do it if they put their mind to it. "When I was in the community of my late master at Tiantong monastery in China, after hearing this truth, while sitting still day and night, the monks thought in times of extreme heat or extreme cold, that they would probably become sick; so they temporarily left off sitting. At that time I thought to myself, ĎEven if I should become sick and die, still I should just practice this. If I fail to practice when I am not sick, what is the use of treating this body tenderly? If I sicken and die, that is my will. To practice and die in the community of a master in the great country of China, and, having died, to be disposed of by a worthy monk, this would above all form an excellent affinity [for a good birth]. If I died in Japan, I couldnít be disposed of by such a person in accordance with the Buddhist ceremony which is in conformity with the Dharma. If I kept practicing and died before realizing enlightenment, from having established this affinity, I should be born in a Buddhist family. If I do not practice, even if I maintain bodily life for a long time, it would be worthless. What would be the use? While my body is sound and I feel I will not fall ill, when unexpectedly I may drown in the ocean or meet an unfortunate death, how will I regret it afterwards?í I remember somebody saying there was a guy that went over Niagara Falls in a barrel, and came out okay. But then he walked down the street in New York and he slipped on a banana peel, and it killed him. [laughter] "I continued to deliberate in this manner, and being firmly resolved, as I sat upright day and night, I did not get sick at all. Now each of you should be thoroughly determined to practice and see; ten out of every ten of you should attain the way. The exhortations of my late master at Tiantong were like this." I remember how difficult it was when I first started sitting zazen. Suzuki Roshi always very gently, so gently, determined that he would raise our determination. He was reflecting Dogenís attitude in this. I remember sitting through those long sesshins in great pain, and, also, wondering if I was sick. There is something about zazen, something about this kind of determination, which brings you through all kinds of obstacles. This is a very interesting attitude of Dogenís, this attitude of, even if I am going to die, this will be the best way; so why save myself for anything else? I think that is the bottom line of single-minded practice. It is not like you should do something like that, but.... You know sometimes people want something. They want enlightenment, or they want some benefit from practice, but everybody comes up against a wall. They always come up against a wall in practice at some place, at some point. And then they say, oh, can I do that? Or I am not sure I can do that, or how do I get through this wall? So when we come up against a wall, the usual way is to go this way, or go that way, but how do you go through a wall? This is a big koan, actually, of our practice. When we meet this wall, how do we go through this wall? And the wall seems like solid concrete for 20 yards, but it is actually a thin piece of paper. And the wall is not there, the wall is here. The obstacle is not out there, the obstacle is right here in our consciousness, in our attitude, in our way of thinking. So, the purpose of practice is to lose your life: it is to die on the cushion. But what is it that dies? It is only our falseness. Whatever is true does not die. The only thing that dies is what is not real. This is called saving ourself. Because when everything falls off, what is left is our true life, which is beyond, which includes both life and death. So yes, we do have to die on the cushion, but what dies is what we call the ego, the false built up delusion of self. I remember how Suzuki Roshi would always drive us to get beyond our limitation, go beyond what we think is our limitation, and by going beyond what we think of as our limitation, bring out deep spirit within ourselves which we ordinarily wouldnít bring out in ourself. We would stop short before we would bring that forth. This is the advantage of having a good teacher who takes you beyond yourself, beyond what you would ordinarily do for yourself. And he also brought out the spirit in a person that brings you beyond your teacher. I remember thinking when I was first beginning to practice that Suzuki Roshi did not like me or he did not feel that I was worthy of practice, which was just my delusion of course. And so I asked him about it. I said do you think that I should continue to practice? I was just kind of testing the water. And he said, "Oh, what is the matter? Isnít it difficult enough for you?" [laughter] If you can find something more difficult you should do that. But I had also made up my mind that I was going to practice even if he said no. In China people would go overboard. In order to prove their sincerity they would cut off their little finger, then tie a rope around their finger and then burn off the tip and do things like that in order to show their sincerity. Dogen has a little something to say about that, which is an extreme that he did not like. He said: "People resolve to abandon even life, cutting off even their limbs and flesh, hands and feet. Such acts are done in insincere manner. Therefore thinking of worldly affairs, many make such resolutions because of a mind which grasps at fame and profit." In other words, people will think you are really wonderful and sincere if you go to that extreme and it works to impress people with your sincerity. "Just meeting situations as they arise, taking things as they come, is difficult. When a student is eager to abandon his bodily life, he should settle down for the moment and decide, in respect to what to say and what to do, whether it is in accord with the truth or whether it is not in accord with the truth. If it is in accord with truth, he should say it, and if it is in accord with truth he should do it." Just take things as they come and what you meet is enough to deal with if you deal with it directly and sincerely. So even this thing about dying on the cushion, and so forth, is simply just meeting what comes. It just means staying with what you are confronted with or what is in front of us, and instead of turning away, dealing with it, and finding a way to penetrate it. It is not doing something extra or something to impress people. It is simply finding the reality within yourself. And then Dogen says, (a pretty long oneÖ) "In ancient times there was a general named Lu Chung-lien who subdued the enemies of the court in the land of the lord of Ping-yuan. Though the lord of Ping-yuan tried to reward him with much gold and silver and other things, Lu Chung-lien refused it all and said, ĎIt is only because it is the way of a general to do so that I attack the enemy well; it is not to obtain rewards or take things.í So he said that he dared not accept." So in other words, my job is just to do what a general does, it is not gain fame or get rewards or be instated in some special way. "Lu Chung-lien is famous for his straightforwardness. Even in the ordinary world, those who are wise simply are what they are and accomplish their own way. They do not think of obtaining rewards. The mental attitude of students should also be like this. Having entered the way of the Buddhas, carrying out various things for the sake of the Buddhist Teaching, you should not think that there will be anything to gain in the way of reward. In all the inner [Buddhist] and outer [non-Buddhist] teachings, they only exhort us to be free from acquisitiveness." So we simply do what we do for the sake of what we do, and we simply are who we are for the sake of who we are. But we donít do something for the sake of something else. This brings to mind what it means to be a priest. Being ordained as a priest is not a reward for something. It is not because, if you practice well and a long time, that you are rewarded and ordained as a priest. Being ordained as a priest is simply a way of life for somebody which is not exactly a way of life for a layperson. Thatís all. It is simply a certain way of life. Although in Buddhism the priesthood is somewhat exalted, a priest is a servant of the Sangha, not someone who should be put up on a pedestal. But the person that wears the robe, they are an example of practice, but as an example of practice, you are there to be criticized by everybody. [chuckle] Well, you know, the person is a priest but they act like this or they act like that. [laughter] So we are kind of on the stage in a way and it forces you to be as sincere as you can be, because everything you do is noticed. Whereas when we are not in that situation, although we are noted, it is not such a big deal. But it is a big deal because people expect the priest to be an example. So it is not really a reward but simply a way of learning something: learning how to be humble, learning humility and learning how to harmonize with everything around you and how to serve and how to be selfless. So, nothing special. As Suzuki Roshi used to say, "nothing special." So be careful what you want. Which brings me to a question: in a Sangha like this, as a Sangha begins to grow and mature, there will be people who want to be ordained and will be ordained. Those people can be like strong pillars of the Sangha because their intension is to support the Sangha and as much as possible to develop practice as a way of life. Lay people also do that. You say why be a priest when you can be a layperson? Or why be a layperson when you can be a priest? There is that fuzzy area in between where they overlap, which is something that is always being worked out. Here there is no division as there is in Asia between what is a layperson and what is a priest. But in Japan, you know, during the Meiji era (1868-1912), the priesthood was turned out of the monastery, so to speak, and were allowed to marry and raise families and that began the temple system in which the monks became priests and tended the family temple, which was just a different way of practicing, but they lost a lot of zazen practice in doing so. In America, our teachers wanted to do zazen, so thatís what they emphasized and that is why we responded because I donít think Americans would have responded to just a Japanese church system. So here lay people practice zazen on a daily basis. It is a very different situation. We try to compare it with traditional Buddhism, which has a division between monks and lay people, but we have to work out a way of practice that encompasses both in a way that takes into consideration our place in time and circumstances of our society. For a long time there will be confusion. But we have to be able to absorb this confusion, to be able to live with a little confusion about what is a priest and what is a layperson until there is some resolution. So we all just have to be patient, and if you are layperson and someone is ordained as a priest, you may say, well, why is that person a priest, and how come I am a layperson? And how come, you know, Iím a priest and that person is a layperson. You can wonder about that, but you donít have to worry about it. [laughter]. It is just part of the process. We are in this process and I think that we should give space to the process and see what happens. So if you are a priest youíre no better than anybody else, and if you are a lay person youíre no better than anybody else. Transcribed by Mary Johnston © Copyright Sojun Mel Weitsman, 2011 |

|