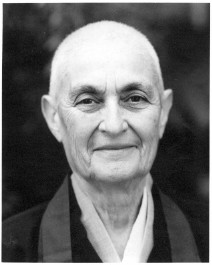

Pain as a Teaching Sesshin Lecture Abbess Zenkei Blanche Hartman |

Good morning. I have been having a little bit of trouble with my knee, so I think I'm going to talk about pain today. I was having trouble with my knee even before I came down to Tassajara for Practice Period, but this morning after a day of sesshin and after sitting in seiza (kneeling position) yesterday for a long time having tea with people, it was feeling particularly unstable. So I thought, "I'll rest it a little bit, I'll sit seiza during breakfast." That was a big mistake. Seiza used to be a resting posture for me when I first started sitting, but somehow I felt extremely unstable and uncomfortable perched up in the air on that cushion, so I changed my position. What I experienced was very interesting to watch: my mind was sort of like, "Idiot, you should have known better than that, and now you're stuck with it for fifty minutes." Every time I leaned over, I felt like I was going to fall over on my head, so I put the cushion down so I could sit lower, and then I started having sciatic pain, and lots of irritation came up. |

My mind was this big mess, and then the soup wasn't hot and the servers were slow. That was breakfast this morning for me. I got back to my cabin and, of course, I don't have any chairs in there. I sit and study in seiza, so it was more of the same. Jack Kornfield has really worked out a very, very well presented discussion of meditation on mindfulness of the body and pain, and a meditation on pain which I would like us to do together today. Don't change your posture, perhaps you've already gotten into a little of your painful areas by now. I hope so, this will help you with this mediation. "Because our acculturation teaches us to avoid, or run, from pain, we don't know much about it. To heal the body, we must study pain. When we bring close attention to our physical pains, we will notice several kinds. We see that sometimes pain arises as we adjust to an unaccustomed sitting posture." (For those of us who are fairly new to sitting, we, in fact, do have to help our bodies become flexible enough to sit in a stable sitting posture. During that time, we may have to make a lot of adjustments in posture, and we may have to change from one posture to another. We may sometimes have to sit in a chair to help ourselves become accustomed to a stable sitting posture. There's nothing in this meditation, and there's nothing that I'm suggesting, to indicate that you should ignore the difficulties that arise from becoming familiar with an unaccustomed posture.) If something arises that's too intense, or too painful, or too difficult to stay with, our mind will wander away. We needn't be worried that somehow we're going to get locked in a room with this thing and we can't get away from it. Our mind will wander away or we will fall asleep. But each time it arises, just stay with it for as long as you can. Little by little, it will lose its potency to frighten us or upset us. Sometimes, very slowly, there are aspects of who I am that are very difficult for me to accept. But just to give careful and kind attention to whatever arises is what our practice is. Sitting facing the wall in sesshin, most of what arises is just our own body, mind, and feelings. We're not interacting with one another so much just now, though we bow with careful and kind attention to each other as we pass, and as we serve and are served. But mostly what we are giving attention to during sesshin is our own stuff. So I want to read you this meditation on healing the body that Jack has in his book. "Sit comfortably and quietly. Let your body rest easily. Breathe gently. Let go of your thoughts, past and future, memories and plans. Just be present. Begin to let your own precious body reveal the places that most need healing. Allow the physical pains, tensions, diseases, or wounds to show themselves. Bring a careful and kind attention to these painful places. Slowly and carefully feel their physical energy. Notice what is deep inside them, the pulsations, throbbing, tension, needles, heat, contraction, aching, that make up what we call pain. Allow these all to be felt fully, to be held in a receptive and kind attention. Then be aware of the surrounding area of your body. If there is contraction and holding, notice this gently. Breathe softly and let it open. In the same way, be aware of any aversion or resistance in your mind. Notice this, too, with a soft attention, without resisting, allowing it to be as it is, allowing it to open in its own time. Now notice the thoughts and fears that accompany the pain you were exploring: `It will never go away.' `I can't stand it.' `I don't deserve this.' `It's too hard, too much trouble, too deep,' and so on. "Let these thoughts rest in your kind attention for a time. Then gently return to your physical body. Let your awareness be deeper and more allowing now. Again, feel the layers of the place of pain, and allow each layer that opens to move, to intensify, or to dissolve in its own time. Bring your attention to the pain as if you were gently comforting a child, holding it all in a loving and soothing attention. Breathe softly into it, accepting all that is present with a healing kindness. Continue this meditation until you feel reconnected with whatever part of your body that calls you until you feel at peace." "Other times pain arising signals that we are sick or have a genuine physical problem. These pains call for a direct response and healing action from us. However, most often the kinds of pains we encounter in meditative attention are not indications of physical problems. They are the painful physical manifestations of our emotional, psychological and spiritual holdings and contractions. Reich called these pains our muscular armor, the areas of our body we have tightened over and over in painful situations as a way to protect ourselves from life's inevitable difficulties. Even a healthy person who sits somewhat comfortably to meditate will probably become aware of pains in his or her body. As we sit still, our shoulders, our backs, our jaws or our necks may hurt. Accumulated knots in the fabric of our body, previously undetected, begin to reveal themselves as we become more open. As we become conscious of the pain they have held, we may also notice feelings, memories, or images connected specifically to each area of tension. As we gradually include in our awareness all that we have previously shut out and neglected, our body heals. Learning to work with this opening is part of the art of meditation. We can bring an open and respectful attention to the sensations that make up our bodily experience. In this process we must work to develop a feeling of awareness of what is actually going on in the body. We can direct our attention to notice the patterns of our breathing, our posture, the way we hold our back, our chest, our belly, our pelvis. In all these areas, we can carefully sense the free movement of energy or the contraction and holding that prevents it. When you meditate, try to allow whatever arises to move through you as it will. Let your attention be very kind." "....Grief, longing, rage, loneliness, and sorrow can all first be felt in your body. With careful and kind attention you can feel deep inside them. Stay with them. After some time, you can breathe softly and open your attention to each of the layers of contraction, emotions, and thoughts that are carried with them. Finally, you can let these, too, rest, as if you were gently comforting a child, accepting all that is present until you feel at peace. You can work with the heart in this way as often as you wish. Remember, the healing of our body and heart is always here. It simply awaits our compassionate attention." (From A Path With Heart© by Jack Kornfield, Bantam Books.) Kind, compassionate, and careful attention is the work of a Bodhisattva. It is the work that allows us to reveal the compassion of the ancestors in our life. Without this compassionate acceptance of "this, just as it is," right here where we are, it's very hard to accept "just this, as it is" in what surrounds us, in those that we meet moment after moment. As we open to accept more of what is here, quite naturally we continue accepting more and more of what is around us until it is all right here. The first three years I was doing zazen, I didn't sit through a single period for forty minutes without changing my posture. I hated myself every time I did it because there were always macho guys sitting, guys and women, and I felt like a wimp over here that kept changing my posture until I got to the point after three years where I didn't have to change my posture. It was during my first sesshin I did at Tassajara, during the middle of the night of the seventh night, that I discovered that, even though I was in pain, I didn't have to move, and there was something else to do with it. In fact, it began to change when I was able to stay with it. It didn't necessarily always go away, but it did begin to change, and then some of the precise location of the persistent pain seemed to be related to particular attitudes of mind that I was holding. Sometimes I would discover what attitude of mind that point of tension was expressing. It was sort of like that point of tension was going to stay there until I got the information about the attitude of mind that was causing it. Then it could also relax, and, in the opening of it, the attitude of mind that I had been holding revealed itself. Actually I don't know exactly how it worked. I just know that there were a number of situations in which particular points of very intense physical discomfort were connected to particular attitudes of mind. One attitude in particular that I was carrying when I came to Tassajara was spiritual pride. I had quit my good job and I had come down the mountains to be a monk and save the world. I thought I was doing something special. As long as I was holding the attitude that I was doing something special, I had this particular pain. When I saw that I had that attitude, the pain become more and more intense. It was in a particular point in my back. It was kind of pressing me down to the floor, and, at a certain point, I was having a conversation with it. I had a notion that it had to do with pride, and then I suggested something trivial and it just got really immense and I heard this voice that said, "You had better pay attention to me or I'm going to break your back." I thought I was really losing it, and then I realized that I had this spiritual pride because I thought I was doing something wonderful for the world by quitting my job and coming to the mountains and sitting zazen and being a Bodhisattva, or whatever I thought I was doing. When I realized that that was the thought I was holding, this particular point of pain just sort of dissolved. "I got it." Pain, and the connection between our body and mind, is very interesting. My knee hurting this morning was partly a reminder that I was being pretty careless and taking my legs for granted. I've been practicing along not being careful about how I was bending it and placing it. When I'm very careful, it doesn't hurt so much. When I push my body around and just say, "Do what I want you to do and don't give me no lip," it doesn't respond very well. The phrase "Waiting it out" came up. In many periods of zazen during sesshin, I get into the mind set of waiting for the period to end. It brings up the question, "At what point, or points, does pain, and what comes up with it, pass its usefulness factor?" So, it is an ongoing question I've had throughout practice. I think that "waiting it out" has an element of aversion and aggression in it, as if you're not ready to give it your kind attention. You just want to grit your teeth and wait for the bell to ring, not giving as much kindness to your body as you are capable of. Rather than waiting it out, there is the possibility of attending to the place where the pain is with your kind attention in the way that Jack described in his meditation. It's the difference between holding still and settling into stillness. In holding still, there is some kind of grippingyou grip the handles of your seat and just hold on until the plane lands. When you can actually give the attention of your heart, and some compassion, to wherever you feel the pain, it may be a different experience than waiting it out. There is sort of stoic quality to waiting it out, and sometimes stoicism is necessary in our life. What I'm suggesting, though, is cultivating some compassion for the painful area and having some feeling of warmth and kindness toward it because it is hurtingyou are hurting: it's you. I'm suggesting there may be some way you can gently turn the attitude of waiting it out into turning toward the pain and caring for it. I recall one period when I was waiting it out and Mel [Sojun Mel Weitsman, Abbot of the Berkeley Zen Center] was carrying the stick. It was the last period of the day. All of a sudden I heard in my mind the most amazing blast of obscenities, language I had not remembered that I knew, directed at Mel because the jerk didn't realize that the period was over and he should put his stick down so that the bell could be rung. It was really blue language; it was quite astonishing. I worked for the Air Force as a mechanic for awhile, and I learned some pretty interesting stuff and it all came out. I was quite amazed. So, "waiting it out" can bring up a lot of old rage and anger, as well, which it may also be useful to take care of in sitting. It's all grist for the mill; it's all the stuff we have to work with. If we see ourselves being stoic, then we just see that aspect of who we are, and we get to examine whether or not that's the most compassionate way to take care of this current situation. Sometimes it may be best to just hang on. There's more than one kind of pain. As you sit, you begin to distinguish between when you need to move in order not to injure yourself, and when it's something that you stay with as long as you can because it has information for you about your emotional life. Reb [Senior Teacher Tenshin Reb Anderson of the San Francisco Zen Center] once said that the reason that the bugs at Tassajara are so bothersome is because we think they are optional, and my question is, "Is zazen optional?" No one can answer that question for you. Obviously not everyone in the world does zazen. Those of us who came here, came because zazen seemed like a practice that had great value in our life, it had transformative power in our life. It's totally a personal choice. There's nothing written in concrete that zazen is the only practice for a monk. It's a practice for which I have a great deal of appreciation, personally, but I may come to a point in my life when cross-legged sitting at least is no longer possible for me. Then I have to find out what zazen means in that situation. Thank you. © Zenkei Blanche Hartman, 1996 |

|