| I often don't remember my dreams, but today

there is a second dream I'd like to recollect for you. I was at Green Gulch and I was

supposed to be giving a lecture. I was going over to the main house, where the dining room

and the kitchen are, looking for someone who was upstairs. I couldn't find the entrance. I

was circling around and it got very convoluted—there were other houses there and all

of the houses were sort of on a cliff by the ocean. I was in a "you can't get there

from here" kind of place. Coming to this impenetrable stone wall, I said, "Oh

gee, I better go back around the other way."Someone at that point came out on their

porch and said, "You can scramble." And I said, "What, up that impenetrable

wall?" And she said, "No, right where you're standing." I looked, and right

where I was standing there was a hole in the wall, and on the other side was the entrance

I was looking for. There's an old story

about a sailing vessel off the coast of Brazil. The crew had run out of fresh water and

when they spotted another vessel they signaled to them to please come and meet them, that

they were out of fresh water, which is a very dangerous thing on the ocean. They were out

of sight of land. And so they signaled, "We need water. We'll send some boats

over." And they got back the signal, "Put down your buckets where you are."

Although they were out of sight of land, they were where the Amazon River empties into the

ocean. It's such a massive river that even out of sight of land, there is still fresh

water. So, "put down your buckets where you are." Our practice and our

realization is right where we are. There is nothing missing right here. In one of the

enlightenment stories in the Dentoroku (Transmission of Light), the stories that

Keizan Zenji compiled of the enlightenment experiences or koans related to each of the

ancestors of the Soto lineage, there is one I want to share with you from Lex Hixon's

translation in Living Buddha Zen (Transmission #40), Tao Ying to Tao P'i:

- The living Buddha Tao Ying enters the Dharma

Hall and remarks to the assembled practitioners: "If you wish to attain a limitless

result, you must become a limitless being. Since you already are such a being, why become

anxious to bring about any such result?"

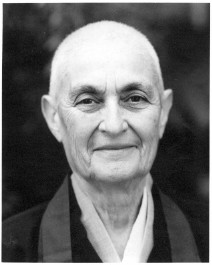

This is like Suzuki Roshi's teaching,

"You're perfect just as you are" or Matsu's "This very mind is

Buddha." So, "since you already are such a limitless being, why be anxious about

such a result?" So are we practicing just to express this limitless being, or because

we think we're not a limitless being? And once we discover we are a limitless being, will

we continue practicing? Well, of course. That's what limitless beings do. This is Dogen

Zenji's practice-enlightenment, practice-realization. This practice itself expresses the

limitlessness which is our essential being. Another one of the stories in this collection

is (Transmission #37) Yao-shan to Yun-yen:

- The living Buddha asks a wandering monk who

appears at the monastery one day, "Where have you practiced?" The successor

says, "Twenty years under Pai-chang." "What does he teach?"

- "He usually says, ‘My expression

contains all hundred flavors’."

- "What is the total expression neither

salty nor bland?" The monk hesitates to make any statement.

- During this moment, the Awakened One breaks

through. "If you remain even slightly hesitant, what are you going to do about the

realm of birth and death that stands right here before your eyes?"

- Becoming more bold, the destined successor

replies, "There is no birth and there is no death."

- The Master says, "Twenty years with the

wonderful Pai-chang has still not freed you from habitual affirmation and habitual

negation. I ask you again plainly, what does Pai-chang teach?"

- Successor: "He often remarks, ‘Look

beyond the three modes of looking. Understand beyond the six modes of

understanding’."

- Master: "That kind of instruction has no

connection whatever to actual awakening. What does Pai-chang really teach?"

- The successor says, "Once Master Pai-chang

entered the Dharma Hall to deliver a discourse. The monks were standing expectantly in

straight rows. Suddenly the sage lunged at us fiercely, swinging his large wooden staff.

We scattered in every direction. In full voice he then called out, ‘Oh monks!’

Heads turned and eyes looked and Pai-chang asked gently, ‘What is it? What is

it?’."

- The Master says, "Thanks to your kindness

today, I have finally been able to come face to face with my marvelous brother

Pai-chang."

In his commentary, Lex Hixon says,

- Yun-yen is not merely repeating his master's

words. He has realized the spirit of Pai-chang's teachings which he reports carefully to

the Awakened One. Hesitating at first to make any statement at all that would limit the

richness of what he has received, only the non-teaching "What is it? What is

it?" has Yun-yen overlooked. Why? Because it is more subtle than the subtle, more

essential than the essential. Under the relentless probing of Buddha Yao-shan, the

submerged memory of this non-teaching arises from early in his discipleship. Remembering

the fierce swinging of the wooden staff, Yun-yen has suddenly become sensitive again to

the dangerous realm of birth and death, which from an absolute point of view, he has

mistakenly dismissed. "What is it? What is it?" Spoken twice, almost in a

whisper, clears away both absolute and relative. This is what our ancient Japanese guide

calls "releasing the handhold on the rockface and leaping from the precipice."

This question comes up again and again throughout

Zen history. This is what Seppo (Hsueh-Feng) asked the monks who came to his gate,

"What is it?" And what Yun-men said, "What's the matter with you?"

What is the business that brings us here? Please investigate this: "What is

it?" "What is it you're doing here?" I don't ask you to look for the words

for it. Words are secondary. I want you to find the feel of it. I want you to find the

fire of it. I want you to touch the source of your life force, to feel the joy and the

love that can come from living from the source of your being. This is taking refuge: to

throw yourself completely into the aliveness of your life. It's pretty risky. You could

lose yourself. There's nothing to hold onto.

In the onrushing, kaleidoscopic chaos of our life

there is nothing substantial to hold onto. Arising moment after moment after moment, we

can't identify with any of it. It arises and passes away. In the midst of the openness of

this question, "What?...What?...What?..." When you touch that really open place,

let it enlarge, let it expand, let it explode your limited view of a substantial separate

self and allow you to experience the boundlessness of your being. Seeing yourself in

everything. This is Tung-shan's "It's like facing the jewel mirror...form and image

behold each other. You are not it. It actually is you." This doesn't mean that when

he saw his reflection in the stream, that he saw that his reflection was him. It

meant that the water was him, the rocks were him, everything...the onrushing stream was

not separate from himself. Wherever he looked was a jeweled mirror. Whatever he saw was

not separate. This is awakening to the totality of who you are and what you are. It's not

that you disappear. You are you and you are everything, simultaneously. The relative and

absolute intermingle and interpenetrate, as we chanted this morning in "Merging of

Difference and Unity." You are you and you are not separate from

anything. It begins with breath. Just breathing in and breathing out. What is inside, what

is outside? Following your breath in your hara, deep at the bottom of your belly,

let it out all the way...let it go completely. Just exhale and don't worry about the

inhale. The exhale will become an inhale, of its own. Trust it. There, at the bottom of

your breath, between exhale and inhale, is a very quiet moment. Stay right there. Be with

whatever arises, right there.

So returning to Tung-shan and his realization, Living

Buddha Zen mentions:

- When Tung-shan was leaving Yun-yen he said,

"In the future, when you are gone and people ask me about your teachings, what shall

I say?" Yun-yen pauses imperceptibly and then softly says, "Just this. Just

this." At this moment, the successor hesitates. The old sage perceives it and warmly

encourages Tung-shan. "You must be extremely careful and thorough in realizing just

this."

- Traveling on foot through green mountains,

pondering just this, Buddha Tung-shan, while wading across a stream, suddenly perceives

the reflection of his own face in the swiftly flowing water. His subtle hesitation

evaporates and he is now prepared to accomplish the transmission of light. He sings in

quiet ecstasy, "Why seek mind somewhere else? Wandering freely, I meet my own true

nature everywhere, through all phenomena. I cannot become it for it is already me."

This affirmation that we're already complete

pervades the teaching of our school. It is the fundamental teaching of our school. Yet

each one of us must investigate it for ourselves. Each one of us must explore, "What?

What can it mean?" Buddha from the beginning. Dogen Zenji's question was, "If

we're Buddha from the beginning, why do we need to practice?" It was a consuming

question for him. He pursued it through practice. Through zazen. Through sitting and

attending to breath. Through becoming completely intimate with his innermost request.

Someone brought up Case 42 from the Dentoroku, Kuan-chih to Yuan-kuan (Doan Kanshi

to Ryozan Inkan):

- The destined successor, background unknown, is

functioning as attendant to the living Buddha, carrying his ceremonial robe. As they stand

together in the Dharma Hall, the attendant opens for the Master this venerable patchwork

robe. The old sage turns and whispers, "What is really going on beneath this

robe?"

- The successor, deeply prepared for the

transmission of light, remains poised in silence. Intensely, the master continues to

whisper, "To study and practice the Buddha way without reaching what is beneath the

robe creates the greatest pain. Please ask me the question."

- The successor repeats the sage's words,

"What is really going on beneath this robe?"

- With almost no sound, the Zen Master responds,

"Deep intimacy." Immediately the successor awakens, places the ceremonial robe

over the shoulders of his master, and performs three prostrations of gratitude, abundant

tears soaking his own upper robe.

- Master: "You have now greatly awakened,

but can you express it?"

- Successor: "Yes."

- Master: "What is going on beneath this

robe of transmission?"

- Successor: "Deep intimacy."

- Master: "And even deeper intimacy."

What is this intimacy? It begins with

yourself...becoming completely intimate with yourself. Through this intimacy with

yourself, the possibility of being intimate with another arises. Because he was so

intimate with himself, Suzuki Roshi could meet me completely when I bowed to him, and jump

up and bow back to me, before I even knew it. When I was remembering that moment, I had

this deep pain, wondering, will I ever be able to meet anyone as completely as he met me?

Wearing this robe without settling the great

matter is indeed the most painful thing. Yet the Hshin Hshin Ming says, "One

in all, all in one. If only this is realized, no more worry about not being perfect."

Please stay close to your breath; stay close to

just this one, as it is. You will find everything you need right here in this moment.

© Zenkei Blanche Hartman, 1997 |